The UK’s Register of Overseas Entities and how to respond to HMRC requests for disclosure

Register of Overseas Entities (ROE) rules require non-UK entities (mainly companies and trusts) looking to buy, sell or transfer property or land in the UK to register with the UK Companies House. The intention of the ROE is to provide UK government agencies with greater insight into who owns UK property and how that ownership is structured.

As a result of the register, HMRC now has access to a vast amount of data about UK property ownership. HMRC has publicly stated it will use ROE data to identify and notify taxpayers who may have undeclared UK tax liabilities as a consequence of having beneficial interest in UK property or land.

These liabilities likely will have been incurred through the UK’s Annual Tax on Enveloped Dwellings, or ATED. The UK announced the ATED in 2012 to eliminate the advantages of enveloping property, or “wrapping” it in an offshore trust or company.

For more context, we outline some of the details of the UK’s ATED in the next section. Before addressing that, however, it’s important to emphasise that HMRC has begun the process of cross referencing its tax records with Register of Overseas Entity data. As part of this process, they have sent notifications to many entities they believe have not complied with ATED and/or non-resident landlord reporting obligations. More entities can expect to receive similar notifications — which are called requests for disclosure — as HMRC continues its review.

Now for some more information about ATED. It will provide some important context for those taxpayers who have registered an overseas entity and have been, or may be, notified by HMRC regarding undeclared liabilities.

Overview of the UK’s ATED

The UK’s ATED is an annual tax reporting obligation introduced in April 2013. It originally applied to companies and trusts that owned UK residential property valued at more than £2,000,000. That threshold has since been reduced to £500,000, which of course greatly increased the number of affected taxpayers under the ATED.

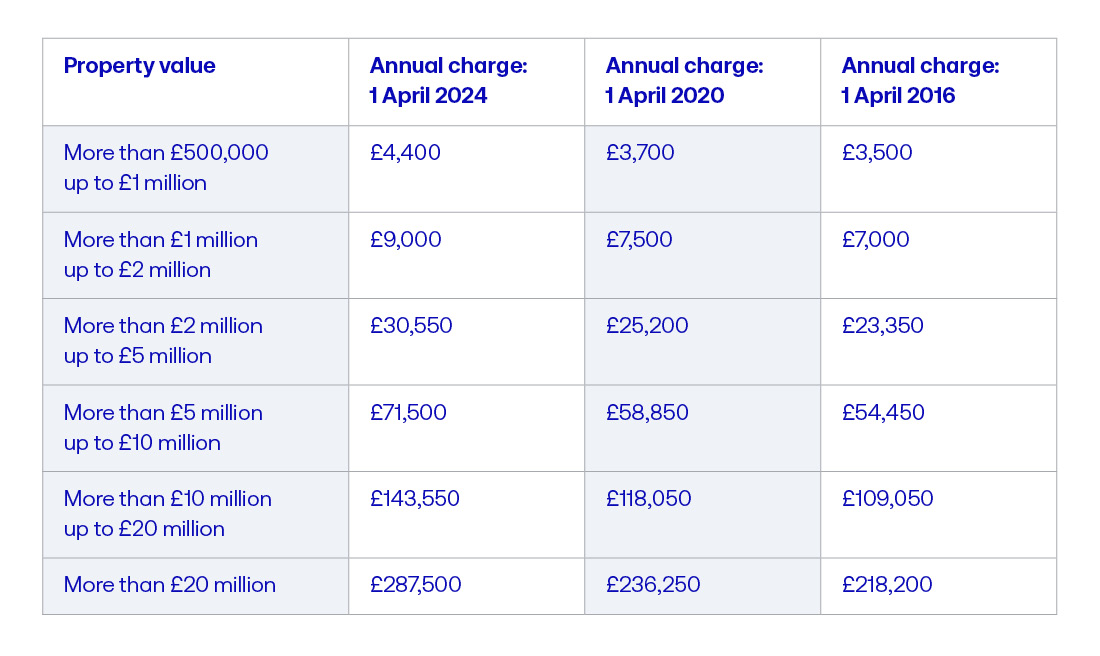

The ATED works on a banding system. That is, tax payable under the ATED is calculated based on the band into which a given property falls, with property values being measured at specific valuation dates. Revaluation dates occur every five years, as follows:

- 1 April 2012, for returns covering the period 1 April 2013 to 31 March 2018;

- 1 April 2017, for returns covering the period 1 April 2018 to 31 March 2023; and

- 1 April 2022, for returns for 1 April 2023 to 31 March 2028.

Chargeable ATED amounts have increased over time. The rates for the periods beginning 1 April 2016, 2020 and 2024 appear below and illustrate how charges have changed since the £500,000 to £1,000,000 band was introduced.

Although ATED returns must be filed annually, it may be possible in certain situations to claim a relief from an ATED tax charge, for example when a property is being:

- redeveloped or held as stock for resale

- rented out to a third party on a commercial basis

- used for certain charitable purposes

When a property owned by a non-UK company is being redeveloped or held for sale, or receives rent, it will likely be subject to corporation tax (CT) reporting obligations and potentially a CT liability under the UK’s transactions in land rules. When a company has received “income from land or property” and CT returns have not been filed, the taxpayer must bring these filings up to date and pay any outstanding CT.

When a UK property worth over £500,000 is owned by a company or a trust, it’s important for the company or trust to monitor its ATED obligations to ensure ongoing compliance. This is particularly important given HMRC’s aggressive targeting of non-compliant entities following its recent review of Register of Overseas Entities data.

Receiving a request for disclosure from HMRC: A real-life example

A request for disclosure is typically a notification from HMRC indicating that it is aware of historic non-compliance; it’s also typically a precursor to a full tax enquiry. If the requested disclosure is not made by the recipient, and the historic non-compliance is not brought up to date in a timely fashion — including back payments and penalties — it’s likely that higher penalties will result.

Vistra was recently contacted by the directors of a non-UK company that had been issued a request for disclosure from HMRC. On reviewing the request and related circumstances, it was clear to us that the company in question had been subject to the UK’s ATED for several years, but the company had not submitted returns or made tax payments.

The property in question had been owned by the non-UK resident company since before the ATED was introduced, and has been valued at between £2 million and £5 million since that time. As a result, the property has been in scope for the ATED since the tax’s inception.

Over the last 12 years, the ATED tax liability for the property in question is projected to be about £285,000. In addition, penalties and interest will also likely be due. As the returns are over a year late and relate to a non-UK company, the maximum penalty is up to 200 percent of the tax at stake, meaning the penalties could exceed £500,000 plus interest. In the end, the company could owe more than £800,000 in combined tax, penalties and interest.

What to do if you receive — or expect to receive — a request for disclosure from HMRC

An entity — typically a company or trust — that receives a request for disclosure from HMRC should immediately seek professional advice to fully understand its potential tax liability, including penalties. The third-party advisor should ensure that the disclosure is comprehensive and accurate after reviewing the details of the property ownership and quantifying the ATED position. It should also look to resolve the historic non-compliance with the aim of minimising any penalties and interest. The third party should also be able to efficiently manage the HMRC disclosure process, including liaising with HMRC.

An entity that has not received an HMRC request for disclosure may expect to receive one in the future if it:

- has registered an entity under with UK’s Register of Overseas Entities;

- is aware that its non-UK resident company or trust holds an interest in residential UK property or land; and

- has not been filing ATED or CT returns.

An entity in this situation should immediately seek professional advice to understand its ATED obligations. If the third-party expert determines that the entity does in fact have historic ATED obligations, it can work with the trust or company to make a voluntary disclosure to HMRC. A voluntary disclosure typically results in a better negotiating position regarding penalties and interest compared to a disclosure made in response to an HMRC request.

Additional considerations: Exiting the UK property market

The reporting and tax burdens associated with owning UK property or land through an offshore company or trust may outweigh the benefits of the ownership structure. A company or trust in this situation may therefore wish to “de-envelope” the property — that is, take it into personal ownership — or simply sell it.

There are numerous options when de-enveloping a property. Consideration should be given to among other things the potential corporation, capital gains and stamp-duty land taxes that may arise on transfer of the property. Here again, stakeholders should seek third-party advice to understand their options and lower their risks.

Tom Blessington, international tax advisory director, and Shoaib Shafi, manager, international corporate tax advisory, contributed to this article.

The contents of this article are intended for informational purposes only. The article should not be relied on as legal or other professional advice. Neither Vistra Group Holding S.A. nor any of its group companies, subsidiaries or affiliates accept responsibility for any loss occasioned by actions taken or refrained from as a result of reading or otherwise consuming this article. For details, read our Legal and Regulatory notice at: https://www.vistra.com/notices . Copyright © 2024 by Vistra Group Holdings SA. All Rights Reserved.